Thirteen centuries ago a small mountain saw the birth of a kingdom

Tradition and history link the origins of the Kingdom of Asturias to two names: Pelayo and Cuadonga/Covadonga, the protagonist and setting where, at the beginning of the 8th century, a series of episodes - true for some and legendary for others - took place, considered to be the first movement of rebellion by northern Christianity against the Muslim power established in the Peninsula a few years earlier. The valley of Cangas de Onís, the Picos de Europa and Mount Auseva would have been witnesses to the rebellion that elected Pelayo as leader -thirteen centuries ago this year-, and who shortly afterwards would star in the legendary war episode (battle or skirmish), on the slopes of that small mountain.

/documents/39908/68682/2291469.jpg/9f6eb7e0-787f-c753-1af1-a15992d9105d?t=1679298470905

Picu Priena in Cuadonga/Covadonga

CUADONGA/COVADONGA, A CRUCIAL SCENARIO

A rebellion that changed history

The Cave of Covadonga and Mount Auseva, in the rugged landscape of the Picos de Europa, constitute the natural bastion that will give shelter to the people who will rise up against the new government established by the Muslims in the peninsula. This first nucleus of resistance - which undoubtedly must not have been the only one, although perhaps the one that had the greatest and quickest success - sought protection in the valley of Cangas de Onís and its projection towards the mountainous interior, in a territory that they knew well.

/documents/39908/68682/2296324.jpg/eaad23cd-5a8a-3596-fd5d-973377d39587?t=1679298453833

Surrounding area of the Sanctuary of Covadonga

This revolt must have sought the leadership of a powerful and prestigious magnate, with property in the region and also with military capacity. It is therefore certain that in 718 an assembly of the main Asturians who opposed the new taxes that the new governor of Gijón intended to impose - in breach of a possible previous pact - elected Pelayo as their leader. From then on, the rebels continued to harass the Muslim power until, a few years later, a punitive expedition was sent from Cordoba, which ended in defeat at Cuadonga/Covadonga.

As the germinal moment of a kingdom that would later achieve great development and prominence, the surviving accounts are plagued with difficulties, legends and biased interpretations that have often been put at the service of self-interested legitimisations, from the 9th century to the present day. But it is precisely these interests that confirm that, thirteen centuries ago today, Cuadonga/Covadonga and the territory of Cangas de Onís were the scene of a chapter of major importance for later history.

Although fairly unknown, the history of Cuadonga/Covadonga prior to the war appears to be steeped in traditions linked to Asturian paganism and its Christianisation. It is not surprising that the present-day Marian grotto was originally a sacred place for some natural divinities, especially female river deities such as Deva - the 'mother goddess' - who gives her name to the river that rises at the foot of the cave. It is likely that in Pelayo's time it was already a Christianised place as a cave temple dedicated to the Virgin.

Pelayo's leadership was undisputed. Despite the difficulty in finding documentary sources from that time, everything points to the fact that he was a charismatic and courageous character, capable of facing the challenge that he must have taken on in the year 718 when the Asturians rose up and elected him as their leader. Then came the battle and triumph over the Muslim army of Alkama, thus creating the Kingdom of Asturias. The first chapter of a new stage in European history was thus written.

The chronicles tell us that a small group of Christian warriors faced a large Muslim army sent from Cordoba. The Asturians made themselves strong on the slopes of Mount Auseva, a strategic place to defeat their enemies who, in their escape through the Picos de Europa, ended up perishing due to the Asturian harassment or the difficult terrain. Medieval writers saw divine favour in these events, and thus arose the legend that spoke of a miraculous victory under the patronage of the Virgin.

Today it is possible to follow the route that the Cordovan hosts followed in their flight, entrusting their escape to the protection of the Picos de Europa. Leaving Mount Auseva, the defeated army of Alkama had to cross the beautiful landscapes of Orandi, the River Cares, Bulnes, Pandébano, Áliva and Espinama until they reached Cosgaya, where a landslide of Mount Subiedes ended up throwing the last survivors of the expedition into the River Deva. See the route

/documents/39908/68682/2291484.jpg/fd2147bf-a29d-af2f-139f-fdabdc349265?t=1679298467107

King Pelayo

PELAYO, "THE FIRST KING OF HISPANIA" The founder of a lineage

In this way, acknowledging that he legitimately held "the first title of king of Hispania", the 15th-century Catalan chronicler Pere Tomic refers to Pelayo. As well known as he is mysterious, since few certainties are documented about Pelayo's life, he was perhaps a representative of the local Asturian elite, or a fugitive Gothic nobleman of supposedly royal lineage, and surely a person with strong family ties among the Asturians. It is even possible that he was subject to the authority of the Muslim prefect of Gijón and exercised some authority in his service after the collapse of Visigothic power. Pelayo ended up leading a revolt (718) that culminated in the battle of Covadonga (722), establishing a small nucleus of power in the village of Cánicas, today Cangues d' Onís/Cangas de Onís: the Kingdom of Asturias was thus born.

An enigmatic figure

/documents/39908/68682/2291356.jpg/dc9bd825-493d-adf0-59bc-b0f0a8e81aed?t=1679298422484

Engraving of King Pelayo

The figure of Pelayo is surrounded by a halo of mystery and legend that is buried in the mists of time. However, the image that emerges is that of a magnate of possible Hispano-Roman or Romanised Gothic origin, with property and prestige in the central-eastern area of Asturias, who may have held positions of responsibility in the final years of the Gothic Kingdom and who initially served the Muslim governor established in Gijón, after the Muslim conquest of Asturian territory from 714 onwards.

The election as leader of the revolt

/documents/39908/68682/2291532.jpg/6d02f351-cb3b-198d-4add-dabb9a024331?t=1679298418483

Engraving of Pelayo and his troops in Covadonga

Pelayo's prestige among the Asturians meant that in 718 he was elected in an assembly to lead a resistance group against the Muslim governor of Gijón, an event that took place in the foothills of the Picos de Europa. Pelayo led a revolt that may have been caused by a rise in tribute from the conquerors after the first few years of domination, although one of the chronicled accounts points to the origin of the revolt being the Muslim governor Munnuza's affronting proposal of marriage to Pelayo's sister.

Pelayo's family

/documents/39908/68682/2291452.jpg/b420d289-8843-0c17-5a41-4cdd7b5d9e89?t=1679298412900

Engraving of Pelayo and his wife Gaudiosa

The account of Pelayo that is handed down in the chronicles and tradition reserves a certain prominence for several women in his family. Firstly, a sister of his - whose name is unknown, although in a false document she is called Dosinda or Adosinda - is said to have been the cause of the Asturian rebellion, when she was sought by the Muslim prefect of Gijón, Munnuza. We also know that Pelayo married a woman whose name is revealed in his first epitaph in Abamia: Gaudiosa. From this couple would be born, in addition to their son Favila, their daughter Ermesinda, who would continue the Pelagian lineage by marriage when her brother died through her marriage to Alfonso I, son of Pedro, Duke of Cantabria.

The mystery surrounding his burial

/documents/39908/68682/2291242.jpg/cd45ba87-5faa-db43-ea24-512d9c50f1ab?t=1679298432068

Church of Santa Eulalia of Abamia

After nineteen years of leadership, Pelayo died in Canicas in 737. According to the 12th-century bishop Pelayo of Oviedo, he was buried in the nearby church of Santa Eulalia de Abamia with his wife, Gaudiosa. Tradition has it that his remains were transferred five centuries later by order of Alfonso X to the Holy Cave of Covadonga, where there is a tomb, dated to the 16th century, which is said to contain his remains and those of his sister Dosinda.

Marbles : "Minima Urbium, Maxima Sedium".

Cangues d' Onís/Cangas de Onís, "the smallest of towns, the largest of capitals".

"The smallest of towns, the largest of capitals" is the motto of the coat of arms - albeit a modern creation - of Cangas de Onís. It thus expresses the historical importance of the small village of Canicas in the early days of the Kingdom of Asturias. Cangues d' Onís/Cangas de Onís would go down in history as the first capital of that Kingdom and even today it still bears the mark of its first rulers and of the notable events that took place there.

/documents/39908/68682/2291308.jpg/e5e36fdb-77ce-bcb9-ba6b-e7c240ed4370?t=1679298462340

Cangues d' Onís/Cangas de Onís from Llueves

The famous episode of the bear that killed Favila

Pelayo was succeeded on the throne by his son Favila, who ruled for only two years. This was due, according to medieval texts, to the fact that he met his death very soon after committing the imprudence of trying to hunt a bear alone, which killed him in the woods near Canicas. Although the exact place where it happened is not known, local tradition assures us that it took place in the village of Llueves, where there is now an inscription that bears witness to that historic event. Tradition also maintains that in the monastery of San Pedro de Villanueva, the Romanesque capitals of its façade tell this story in stone.

Apart from his unfortunate end, Favila's life is also known for his patronage of the Chapel of Santa Cruz in Cangas de Onís. Thanks to its foundation stone - now lost - we know that in the year 737 this temple was consecrated by Favila, his wife Froiliuba and their children. The church - now much restored - was erected on top of a Neolithic dolmen that is still visible, probably with the intention of Christianising a place of great spiritual importance for the region. According to later legends, the cross raised by Pelayo in Cuadonga/Covadonga and later covered with gold and jewels by Alfonso III was kept here: the Cross of Victory.

On the death of Favila, Alfonso I, son of Duke Pedro of Cantabria and son-in-law of Pelayo, took the Asturian throne, having married his daughter Ermesinda. According to the chronicles, under Alfonso I the opposition of the Asturians ceased to be merely resistance and became a direct confrontation with Muslim power, occupying the area to the north of the Cantabrian Mountains and making several incursions into the Duero valley. He died in Cangas and was buried, according to tradition, in a "monastery of Santa María", identified with the Sanctuary of Covadonga, in whose cave he rests today with his wife. However, he had previously founded a church in the vicinity of Cangas that would be the precedent of the monastery of San Pedro de Villanueva. The origins of this monastery are closely linked to the figure of Alfonso I, as tradition has it that the monarchs built a church and royal pantheon in Villanueva, to which they gave the title of the monastery of Santa María. Archaeology has given some certainty to these links as architectural and material remains from the 8th century have been identified under the site of the Benedictine monastery.

The old parish church of Cangas de Onís is a monumental 16th-century building, which still preserves interesting Renaissance and Baroque mural paintings inside. Closed for worship in 1963, since 2006 it has housed the Aula del Reino de Asturias, an interpretation centre where it is possible to take a complete tour of the history of the Asturian monarchy. Through various audiovisual resources, panels and models, as well as games designed for children, the centre provides an insight into the history of this period, which began with the proclamation of Pelayo as king in 718 and the subsequent battle of Covadonga in 722, until the transfer of the court from Oviedo to León in 910. The different stages in the history of the Asturian kingdom are reflected in a modern facility that is a must-see for all lovers of history, art and Asturias.

A symbol of Asturias and a constant source of creativity.

Pelayo and Cuadonga/Covadonga represent the essence of a cultural identity

Pelayo and Cuadonga/Covadonga constitute the germinal story of the origins of a Kingdom that is the forerunner of the medieval peninsular kingdoms, the origin of our country as a historical reality and even the start of a mission of Reconquest that would be consecrated as an identity element par excellence. For this reason, from the time of the Asturian Monarchy itself, Pelayo is recognised as the origin of it.

/documents/39908/68682/2291231.jpg/0912b102-c9d0-1360-5abd-a21c0836d3a4?t=1679298413705

Surrounding area of the Sanctuary of Covadonga

A symbol of Asturias and a constant source of creativity.

Thus, the story of Pelayo and his uprising and victory at Cuadonga/Covadonga have been a source of inspiration for new legends and all kinds of artistic, written and plastic manifestations. There have been many plays, poems, novels, paintings, sculptures, films, etc. in which Pelayo and Cuadonga/Covadonga/Covadonga have provided the plot and image.

Their importance has been such that, throughout history, artists from Asturias, but also from the rest of Spain and from many other foreign countries, have contributed new visions of these episodes in line with the successive artistic and cultural currents. Pelayo and Cuadonga/Covadonga have been enriched by all of them and have become a symbol that over the years has had all kinds of representations and uses.

The Victoria Cross

/documents/39908/68682/2291324.jpg/244abf60-402f-fba0-6bb7-1b65db1f2a9a?t=1679298435384

Victory Cross

The Victoria Cross and the Roman Bridge - also known as the Puentón - in Cangas de Onís are unmistakable symbols of the history of Asturias. The Roman Bridge is located over the river Sella, which is also closely linked to the life of Pelayo and his deeds, and from its main arch hangs an enormous Victoria Cross, which reminds us of the historical and now mythical episode that gave birth to a small Kingdom, which had its first seat in the always hospitable Canicas, today Cangas de Onís.

The link with the monarchy

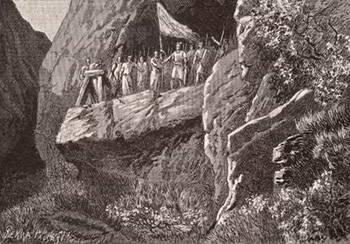

/documents/39908/68682/2291500.jpg/9f4fa9ba-0812-cf0c-2950-f48d982ef624?t=1679298442614

Commemorative postcard of the proclamation of Felipe de Borbón as Prince of Asturias

Pelayo and Covadonga and the story of their epic - still often steeped in legend - has become, over the centuries, a true symbol of the identity of the whole of the Asturian region. The deeds of Pelayo and the Asturians are depicted on many of the coats of arms and emblems of the towns and councils of Asturias, and such a deep-rooted historical symbol as the Victoria Cross is related to a supposed cross raised by Pelayo at Covadonga. The Spanish monarchy, despite the dynastic changes over the centuries, has its roots in Pelayo and Covadonga. Since the 14th century, the heir to the Spanish crown has borne the title of Prince of Asturias, and it was at the Sanctuary that the current king, Felipe VI, was sworn in as Prince of Asturias in 1977.

Inspiration for literature, music and cinema

/documents/39908/68682/2291437.jpg/ac8f6f5d-4f75-9a3c-7ef2-dc5bc4e83a35?t=1679298471689

Poster of the film: This is Asturias. Photo: Museum of the People of Asturias

Numerous playwrights, poets, novelists, musicians and filmmakers have been inspired by the myth of Pelayo and Covadonga. From the Renaissance and the Spanish Golden Age to the present day, plays in epic, comic, tragic or romantic styles have fed the world of culture. Likewise, poets have seen in Pelayo and the epic of Monte Auseva an inspiration for their verses, and illustrious names such as Espronceda and Campoamor have been seduced by this myth of myths.

Cinema and music have also looked to this mysterious and charismatic story for their creative germ, and Pelayo has even been the protagonist of an opera.

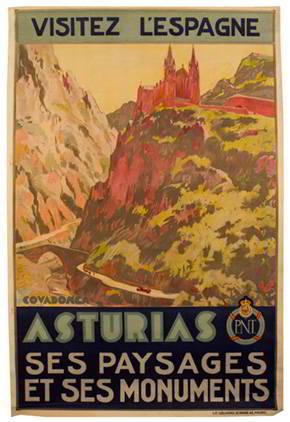

A myth recreated in the visual arts

/documents/39908/68682/2291275.jpg/87d5dd03-0f87-e961-dfa7-2904ab488125?t=1679298412071

Poster for the tourist promotion of Spain in 1929. Photo: Museum of the People of Asturias

The mountains of Covadonga, the Cave, the Basilica, the landscapes of the Picos de Europa, the people... In short, this now eternal myth has been recreated hundreds of times in the plastic arts. Paintings, engravings, sculptures, coats of arms, photographs, posters, labels, etc. have been the medium that has spread this great story throughout the world, making imagination and creativity the best tools to show all the beauty and countless nuances of an event that many centuries later -thirteen- continues to be an inexhaustible source of inspiration.